Typically, an Alternate Reality Game (ARG) is "an interactive networked narrative that uses the real world as a platform and uses transmedia storytelling to deliver a story that may be altered by participants' ideas or actions", as per the Wikipedia definition.

This is the method we are currently applying at Zorean to develop the real-world forensic adventure gameMark Lane's Logs: Project H.U.M.A.N.. We could call it a Forensic Alternate Reality Game (FARG).

The Concept

This is a post-event game, that is, it's about knowing as much as possible about something that already happened. It's about forensics.

Imagine that something had happened. Something big. Traces of that event have been left on the Internet, by people and organizations that were involved. Text, codes, photos, documents, chat logs, clues, riddles. Anywhere on the Internet.

In our design, you start with just a SMS message from Mark Lane. From there, you have to reproduce Mark's steps, find what he found, and live a discovery adventure just like he did. The idea is to make you feel you're uncovering a real case. The SMS message is what's called in ARG as the Rabbithole.

Then, there is no software supplied by us. Unlike a traditional game where you must download and run an application, there is no such thing with our approach. The initial package we must supply will contain information about how to start the game, and some initial clues.

You are enticed to take the challenge and go out to cyberspace looking for things that will help you discover and solve the case. The truth is somewhere out there, on the Internet. You're out in the wild. The Internet is millions of times bigger than a computer game sandbox...

Your forensic investigation job is to be as close to reality as we can make it. For those gamers that only like to be firing five rounds per second, this will be dead boring. But to mystery addicts, the concept brings the puzzle adventure type to a whole new level.

The Mechanics

To play, you use one or more devices of your choice (computer, laptop, tablet or phone). Specifically related to the game, you have nothing installed in your computer, except probably for the initial package.

The game's underlying challenge is to progress as much as possible in the investigation. To progress in the game you must work as a forensic investigator. As such, you will need to, among many things:

- Find and read Mark Lane's logs (the game's spinal cord)

- Visit websites

- Download files

- Classify and organize collected evidence

- Take notes

- Solve puzzles, riddles and encrypted messages

- Perform deductive and logic thinking

Each piece of evidence found *may* help you discover a part of the story, solve problems and riddles, that might lead to more evidence, helping you progress further. You might stumble upon some "fillers" to confuse you. After all, forensic investigation progresses on confusing information.

The more evidence you collect, the higher you will score. Any piece of evidence is a game item, a file that you store on your device (or in the cloud, if you choose to). Clues are found on these pieces of evidence, or anywhere on the Internet.

Unlike traditional games, where most of the game is installed or downloaded, in this game you start with an initial package of a few kilobytes, and could end with a few megabytes of evidence on your device.

Scoring

You are scored in two ways: a global numerical score and a completeness score. The global score is calculated according to several factors, including the type of collected evidence and the time taken to find it. Harder-to-find evidence is scored higher. The completeness score is a percentage that represents how far you have progressed in the game.

Making It Visual

Just because there is no game running in the traditional sense, it doesn't mean there are no visuals. In fact, creating a visual experience in this type of game is imperative. The way we found to make the game much more appealing was to have Mark taking photos on his mission. This gives you the true sensation of being there. They're like stills from a movie.

Some photos we licensed, others we had to shoot them yourselves, especially those that show unique aspects of the game.

The Timeline

Because our Forensic Alternate Reality Game (FARG) is a post-event game, a precise timeline can be defined. In fact, it has to be. The entire game will be driven by it.

The story timeline will be split into many steps. In our design, Mark constantly registers every detail of his mission on his rugged tablet. We call each of these steps, a log (hence the game name Mark Lane's Logs). These logs have a sequence. We call it the mainline.

How will the game events (or the steps) be found? We have chosen a non-linear approach: you might advance in the timeline before achieving previous steps. This increases the game's difficulty a bit because you have to be careful about the order of the narrative.

Location

Never heard of the space-time continuum? It exists everywhere, and our game is no exception. Besides setting a precise timeline, you must determine the precise locations for every timeline step. This is very important as it will help you "be there, at the right time".

Being a part of the investigation efforts, location is also a game item. We set a location for each of Mark's logs, so we took the opportunity to add this aspect to the game. In our design, you must associate a precise location for each of Mark's logs.

How precise must be the location? We went as far as finding the precise location of several shops Mark will visit. And when we mean precise, we mean like ten-foot accuracy!

The Puzzles

The puzzles included in the game are very diverse. I mean, you can find virtually anything you can remember of. One key design principle is to chain puzzles by their difficulty level. Otherwise gaming experience will suffer and the game may feel weird.

From a simple crossword puzzle to an encryption table, anything can be found. I won't show any examples here. There are plenty of examples around on the Internet.

The Clues

Clues will glue the game together and are very, very important. Another critical factor is, how will you know something you find is a clue? A clue is something useful. Before your eyes, everything might look equal. Everything might look useful.

Clues can be presented directly in another game item, or they can be implied. Implied clues can be "zoomed in", that is, there is some kind of selection factor that will narrow your search.

Trial-and-error is the life of a forensic investigator. It's part of the game.

The Clue System

So, how can we make sure you can follow the leads, find clues and progress in the game? And, more importantly, how to make the game accessible to both the "amateur" and "professional" investigators? And even more importantly, how to make yourexperience enjoyable and challenging to all skill levels?

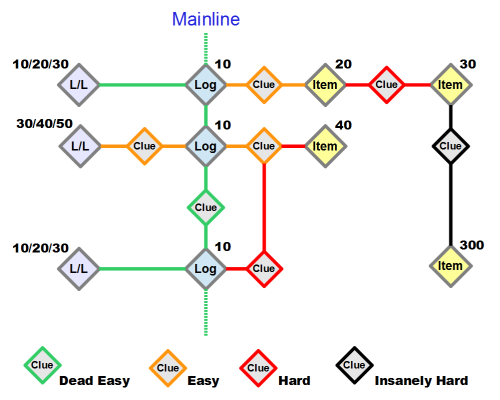

The answer lies on an inverse fishbone diagram:

Well, it's not really a fishbone diagram. But it's close.

This is the heart of a FARG. The game's mainline must be the easiest part to solve and find. Alternate Reality Games are essentially networked narratives, and these narrative pieces should be the easiest pieces to find, essentially because they drive you along the story.

All game items are chained together. To be found, one or more clues have to be identified and combined if necessary. It is then increasingly difficult to find subsequent game items on the same discovery path.

Note that in our design we don't score clues. Only collected game items are scored, based on our judgment on how hard it might be to reach them. Locations (L/L) are also scored, but here we add a precision factor. The more accurate you get, the higher the score will be. The numbers shown next to the game items are their base score. It's called a base score because there are other factors that are applied, like "time erosion": the later you are, the less valuable is the clue.

This system allows less skilled players to play and progress, getting challenged by the intermediate difficulty puzzles. Hardcore players will get the chance to beat the really hard challenges prepared for them.

Real World Development

If we want to make the experience believable, sooner or later we would bump into the need of building real-world stuff. Yes, physical things. Things you can touch. But... what for, if the game is played in "cyberspace"?

As you know, you won't find nothing original in this world unless you create it. And that's what we did! For instance, the secret society Mark will unveil exchanges messages using an ancient cryptographic tool. For this we invented a completely new crypto system, and a new "machine". Unfortunately I can't show it before the game's release. This is something original.

These are real-world things we have to prepare, sometimes just to take a single photo. We can't show you more than this before the game is released.

Painting objects for use in the game

Building an original "ancient" crypto device

Laying Out the Game

Because the underlying concept is forensic investigation, everything in the game's story has already happened. Contrary to most games, you don't set the story, and have no influence in it.

Your job is to investigate. Something that is already "there". The traces that have been left on the Internet are set before the game launches. This has to be planned in advance, of course.

Making It Real

In a real-world forensic adventure, you might put some answers on a news story on CNN or on the New York Times. Something about a real company or real person might help the player proceed. The ultimate idea is to intertwine the game with your own reality so that you'll be left wondering if the story didn't actually happen...