The Piltdown Macro

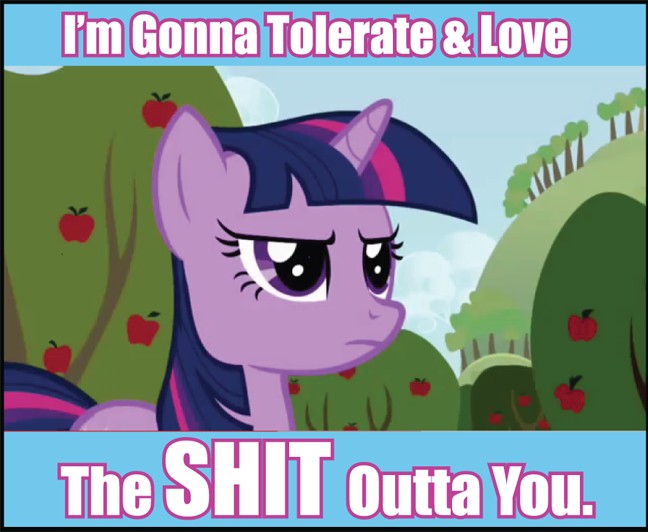

Here’s what documentarians and pop-culture journalists almost invariably stumble upon when, through digital archaeology and earnest interviews, they try to understand how the pony fandom got started:

It’s perhaps the canonical image macro dating from the early days of the 4chan-based pony fandom, back when such macros were the primary way in which nascent fans communicated to each other that they were paying just a bit more attention to My Little Pony than one might think necessary to make a few visual Internet jokes from it. It was both a defensive mechanism and a rallying cry for fans reveling in the odd rebellious thrill of it all, and soon to “love and tolerate” naysayers became as synonymous with the show’s online fan base as the once-witty term “brony”.The narrative that these artifacts imply is compelling: Early fans of the show congregated around its message of colorblind inclusiveness and drew strength from it, enough so as to ward off the mockery of their peers, both online and off. “Trolling” was met with indulgent smiles. Invective and insults earned only forgiveness. A new era of peace and understanding bloomed on the Internet, all thanks to the powerful, irresistible message of Love and Tolerance preached by Lauren Faust’s pony show.There’s only one problem: The show is about no such thing.You’d think, from all the play that “love and tolerance” gets among fans trying to explain the appeal, that it’s a catchphrase that shows up everywhere, in episode after episode, a message that’s drilled home repeatedly like safety admonishments at the end of G.I. Joe cartoons in the 80s. But it’s not. The ponies don’t love one another unconditionally. They don’t make a point of putting up with each other’s differences. The word tolerance never even occurs anywhere in any episode script.Oh, sure, there’s plenty of friendship in the show. There are Elements of Harmony. There’s a “Smile” song. But a journalist who knows nothing about the show doesn’t know the difference between those things, which fans recognize as refreshingly innovative and endearing character-defining plot elements, and the sort of cynical, didactic moral message of tolerance that infested so many preachy “educational” cartoons of past decades that the very concept was played out by the mid-90s.Fans who perpetuate the “love and tolerance” meme do so without acknowledging how profoundly unlike those older shows FiM is. In the process they give those who seek to understand the show’s appeal among animation-loving adults the impression that this is just the latest in a long line of aggressively wholesome “message” shows, hamfistedly teaching children the value of inclusiveness and open-mindedness through rampant tokenism and repetitive storylines about the perils of prejudice. To someone running an interview with fans to learn what’s so great about a show about ponies, finding out that it’s apparently about “love and tolerance” is like hearing that a modern clumsily disguised edu-tainment show in the vein of Captain Planet or The Magic School Bus has somehow, for no discernible reason that makes it unique, managed to transcend its genre and strike such a chord among nostalgia-loving children of the 80s that they now stage conventions across the country and attend them in the thousands.I’d like to caution would-be brony-fandom journalists against making this assumption. If someone you interview tries to tell you that “love and tolerance” is some kind of central theme in My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, ask him what that message has to do with the show. Ask for specific examples. I’ll bet the answer you get won’t be very convincing.

Don’t Judge a Show By its Fandom

I’m not here to argue that fans of the show don’t live by the “love and tolerate” mantra the way they say they do, or to commentate on whether it’s hypocritically applied only to the fandom’s interactions with some adjacent Internet subcultures and not to those with others. Some folks might find such a discussion rewarding. But what I’m doing instead is pointing out that the slogan, while it may be an admirable one, only has the barest of connections to the premise of FiM—no more so than to any of dozens of other cartoons that have been produced in the past thirty years or more.Plenty of ink has been spilled, here and elsewhere, over what it is that draws fans so irresistibly to the show—whether it’s the animation, the characterizations, or more generally the idea of a firmly girl-oriented show with such genuine quality and broad appeal that the novelty of watching it gives it a thrill rather than a deal-breaking stigma. One thing it surely isn’t, though, is that the message of the show is all about such a facile and ultimately unconvincing concept as tolerance.

Be honest: does this image inspire you, or does it make your lip curl in an involuntary sneer?

In fact, nowadays using the word tolerance is a surefire way to get your audience’s eyes rolling. It’s a punchline, not a philosophy. It’s the stuff of parody and mockery, and nobody takes it seriously.Worse, embracing tolerance as an unironic byword isn’t a great way for a fan to convince others that he’s a discriminating fan of quality content, or that FiM is by extension unusually good or worth watching. Rather, it suggests to the disinterested third party that it can’t be the show itself that’s so appealing—that it’s more likely something about the online community or all the meta-material that the community has produced that is behind the real draw. Saying it’s about “love and tolerance” just makes a non-fan question one’s judgment and taste.It’s particularly a shame because the show’s real premise can indeed stand on its own, if it’s described with more appropriate vocabulary. I believe most fans understand implicitly that it isn’t the cast’s determination to welcome ponies of all shapes, colors, sizes, and backgrounds in their tea parties that makes them into compelling vessels for storytelling. Far from it. It’s actually their very human conflicts that lie at the heart of their appeal, the interpersonal incompatibilities that they learn to work around rather than accept unquestioningly.It would be simple, too easy in fact, for the show to put forth a message that the kids watching the show should learn to just “get along” with their classmates, that anyone can be a friend no matter what they look like. This is hardly untrodden ground in kids’ programming. Generations have been inundated with this message,

Some people just aren't worth tolerating. Really.

Considering that FiM is at its heart a “self-help” show in many ways, seeking to teach kids viable real-life lessons to put into play on the schoolyard, it’s hardly surprising that the “don’t judge a book by its cover” lessons—like the one centered, perhaps predictably, on Zecora—are the exception rather than the rule, taking up a small proportion of the show’s attention commensurate with how often such lessons actually prove useful in the real world. The show instead chooses to spend its time on much subtler, more interesting lessons such as how to distinguish a true friend from someone who’s only trying to butter you up to get something out of you, or how to learn where your limits are and how to let your friends rescue you when you find yourself beyond them. This is tricky subject matter, often more applicable to the lives of adults than of kids—and a far cry from the superficial message about “tolerance” that a casual observer, knowing the show more from image macros than from spending time actually watching any episodes, might assume pervades its storytelling.This is in fact one of the things that’s innovative, even “postmodern”, about FiM. A traditionally “tolerance at all costs” show would preach that message by telling the audience that if there’s something about a weird-looking newcomer that rubs you the wrong way, then that’s your problem, it’s your failing—it’s never the newcomer’s. This is part of what has made us as a society so cynical about that kind of message these days: it criticizes us, preaches at us, puts us on the defensive. But FiM takes a different tack altogether. It gives kids in the audience an entirely different message, telling them that they’re the ones who deserve love and friendship and shouldn’t have to change for someone else’s sake, and yet that they should still work to eliminate their own inevitable flaws as they discover them. It’s self-affirming, and at the same time prescriptive, holding up a high standard of behavior to which to aspire. The self-improvement nature of the show gives kids the measuring sticks against which to judge themselves and the tools by which they can improve, and it casts those newcomers—like Gilda and Trixie—who don’t measure up, or who don’t agree to even try, as the forces of villainy, not poor misunderstood souls who just need to be given a chance. You have to deserve to have such good friends as Twilight and the gang.Many of the most compelling stories in the FiM canon are the ones where the ponies have to work the hardest to overcome their personal failings, often because they fear being ostracized or losing their friends’ valued trust and confidence otherwise. Fluttershy’s character arc, for example, throughout the first two seasons centers on her slowly gaining self-confidence and assertiveness, often under the exasperated glare of her long-time friend Rainbow Dash. What makes this piece of ongoing narrative entertaining on so many relatable levels isn’t that Rainbow tolerates her; that much we expect at the very least. It’s that there’s the very real threat of Rainbow getting entirely fed up with Fluttershy and leaving her to find her own way. We see what kind of high-stakes pressure Rainbow Dash faces as the go-to pony for feats of heroism and bravery, and she can’t always afford to make concessions for Fluttershy if she can’t pull her own weight. It’s an entirely plausible possibility that Fluttershy might simply not measure up to Rainbow’s standards, which is what makes her long struggle to meet those standards so poignant and her successes so rewarding.This isn’t tolerance. It’s the opposite. It’s human nature.We’re not wired to be tolerant; we’re wired to appreciate those around us who can give a good accounting of themselves and be worth our while to know them, especially in the demanding, unforgiving grown-up world. Any attempts that modern popular media makes to cajole us into tolerating those who don’t meet our standards are not appealing to any innate impulses in us, but rather are imposing an artificial constraint on the nature of our minds.My Little Pony knows this. And it’s succeeded in earning such a sizable adult audience because of that deep understanding of how the human mind works and its ability to exploit it—not because it’s following the same tired script whereby we’re supposed to learn to ignore our instincts and give people the benefit of the doubt.Every time we see Twilight Sparkle force herself to become a more sociable creature for the sake of her newfound friendships, or Rarity and Sweetie Belle each making concessions in order to meet each other halfway, we’re reminded of what is of value in Pony world: the highly realistic standards of a grown-up social environment. And when a new face shows up in Ponyville, such as Cranky Doodle Donkey, we’re given refreshingly original angles on how introductions ought to be made. Pinkie Pie, tolerant to a fault (as we saw in her attempts to justify Gilda’s behavior), all but becomes the villain of the episode in which she harasses the poor donkey to within inches of his sanity, all to keep her perfect record of friendship unbroken. By the time the episode concludes, we’re on the brink of writing Pinkie off as having burst the limits of our—and Cranky’s—tolerance of her.

Surely you know that to "tolerate" something is to approve of it unconditionally.

“Tolerance”, then, is a shallow, overused, almost meaningless term nowadays, one that people simply assume is a good thing because of its pervasiveness in our society and pop culture. Don’t get me wrong—being inclusive and open-hearted is a wonderful thing, and I’m by no means arguing that people should be prejudiced toward newcomers from unfamiliar backgrounds. But we ought to be careful with our definitions. There’s a reason why South Park devoted an episode toward the “Death Camp of Tolerance”, a bitingly satiric way to drive home the point that tolerance does not and should not automatically imply approval—and that being successful in a social world involves far more involved skills than simply learning not to mistrust others reflexively because they’re different. Sometimes you have to change, and sometimes you have to insist that others change, because—as FiM illustrates so vividly with the examples of Gilda, Trixie, Diamond Tiara, and others—some behaviors are just not OK. Tolerating them just makes matters worse.

The Unreliable Narrator

When you know the show well, hearing fans speak of it as though its grand revolutionary premise is its message of love and tolerance toward your fellow man becomes downright bizarre. That’s why, as researchers and journalists from all over the land begin to converge on the Pony fandom to find out what makes it tick, and now that Hasbro itself is beginning to incorporate fan-created memes into its own merchandising, I’d like to remind seekers of understanding to watch the show themselves before interviewing fans for their insights. I’d like to see them decide independently, from first-hand observations, whether the answers they hear for why the show is so appealing make sense to them. Whether fans are prone to reciting a misleading catchphrase as the distilled essence of the show, suggesting that they appreciate it on some semi-ironic meta level (i.e. that a presumed “love and tolerance” message helps them cope with mockery from others on the Internet or on campus), or whether they have a more coherent answer that’s more firmly grounded in the show’s reality, is a fairly important distinction to make in understanding the show and its place in the entertainment landscape. Ultimately, whether fans can articulate why they love the show in a convincing manner might make for a salient point in one’s thesis—perhaps the show still, to this day, after two complete seasons, has managed to remain an inexplicable enigma even to its most devoted followers.But that’s neither here nor there. What I want to reiterate more than anything else is simply that if My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic were truly about “love and tolerance”, it would be nowhere near as special as it is. What makes it so special, indeed, is how firmly it rejects such a philosophy and strikes out in a direction we’ve seen so seldom, not just in kids’ entertainment, but in anything on television in recent memory.It took each of us several episodes to gradually come to understand what kind of a show this was that we had coaxed, cajoled, tricked ourselves into watching. It was certainly like nothing we’d ever encountered before, and to this day it remains a tantalizing mystery exactly what strokes of unprecedented inspiration lay behind its unique conception. It’s still a surreal experience to many fans. It’s small wonder that we’ll grasp for something, anything, recognizable that helps to explain the show or that allows us to present it to inquisitive friends and colleagues in a way that they’ll understand.But be that as it may, it would be a terrible mistake for those who seek to understand the phenomenon of Pony fandom to conclude that the reason why it’s so great is that it’s just doing what every other show from the past thirty years has tried to do.

Man, this was a pain in the a$$ to format and to make it look right, but I think I got it :)

I know it's long, but please have a read, it makes some good points on the phrase.

very good article, hopefully it will get in the hands of someone from the new york post

I, uh, skimmed it- so this comment might be a bit misinformed.

I wouldn't call it a show about "Love and Tolerance", I view that phrase as more of a fandom meme.

Part of it is about how outside of cultural stereotypes and norms the Brony movement is, and how the "Don't judge a book by its cover" inherent step most of the fanbase takes extends into the fanbase.

Part of it is a hilarious way to counter-troll, though I've never done that.

(I ain't goin to 4chan, ever.)

Yeah, the whole "Love and Tolerate" thing was more of a fandom thing. The article even says "Love and Tolerance" was just a fandom thing.

The point of the article was getting it out that the show does not teach "Love and Tolerance" and therefore should be respected for it's different approach to dealing with problematic people (for instance how they got rid of Gilda, Trixie, and all the other villains). FiM has shown that there are limits to tolerance and when broken, the offender should not be tolerated and removed from society.

Whenever I try to read this, everything else suddenly becomes more interesting.