Tears of Avia is a game produced by a very small team of people who actually have full time jobs. Currently Andrew Livy is fronting the majority of the development and pumping pretty much all of his earnings back into the project.

We want to push the game to the next level, here's a post-mortem / ramblings of our experiences on some of the things that went right and some of the things that went wrong in the past few months so that others may (hopefully) learn from it.

Planning and Social Media

Simultaneously launching on Greenlight, Kickstarter as well as going to a trade show like EGX was always on the cards. Even when Tears of Avia was barely a few lines of code this was the original plan. Back then, I didn't even have a twitter account - if you don't have one then you should get one too.

Part of the planning is to read (like you are now) many articles and post-mortems on the Internet of both successful and unsuccessful campaigns to help prepare you to avoid making mistakes others have done so.

Exposure

One of the biggest things I knew that I needed in order to make a success of the game is exposure. Lots of people were screaming from the rafters about how good twitter is, and to an extent it's true but with a caveat: It's only about as good as 1% of your follower list. You need to have one heck of a following to even make the slightest impact.

I had people on facebook contact me late into my campaign after seeing a friend post about it on facebook. This person was a friend on Twitter and never saw any of my tweets. Twitter moves at a million miles per hour, so most of your content only gets seen in the split second you actually post it - that's the drawback of Twitter.

I advertised the Kickstarter campaign on both Facebook and Twitter, out of the two platforms Facebook seemed to have better reach although it is uncertain if that audience actually exists because there's allegations that facebook responds to campaigns by the use of bots. Some of the people who responded to the campaign definitely seemed like real people though.

EGX 2015

EGX was the first time I had ever exhibited at a game trade show. In the years prior I attended both Gamescom and EGX 2014 as a visitor to see what sort of footfall there was, how people ran their stands and I spent some time chatting with developers about their experiences.

When we applied for EGX, our main artist Pinax was still in crunch mode working on the Aldnoah Zero manga adaptation, so his time was massively limited. Despite this, we worked as hard as possible to bring the game to a state we could put in front of players. It wasn't perfect and was still a 'dressed up prototype' but players enjoyed it. A lot!

Only a small handful of players were hypercritical. It's important to take this feedback and use it in a way that can help you improve the game. Much of the feedback were on issues that I was already painfully aware of but simply lacked the time to implement in time for the exhibition, but some new things were suggested that were really valuable.

Exhibitions are not cheap. Our stand was a single booth space, with the backing board and PC hire (we don't have the means to transport our own) the space itself costs £1200 total including tax.

Bearing in mind you'll also want to get a hotel and cover food costs (which are often expensive around exhibition centres) you're looking at spending quite a lot. If you're thinking about Gamescom, you can multiply that figure by ten.

Getting Press Involvement

This was something I was keen to tackle. I read every page on PixelProspector (you should too), made a presskit, press releases, a big old list of press contacts aaaaaaand.... nothing. Well, almost.

The main press that covered us did so of their own volition with no prompting from myself, but none of the big sites care about game Kickstarter campaigns or anything that is far from complete. They want to see your game from start to finish in order to review it. It's a real catch-22.

One of the reviews we got was as if the game itself was a completed product, so all the early prototype flaws and oddities that were yet to be ironed out ended up working against us leaving a rather scathing review. It was unbiased and the game did have these flaws at the time of writing, so if your game is underdeveloped and you need to get the press to write about it then you might do more damage than good by giving them a copy to check out.

Most of the press attention we got was from bloggers who were genuinely interested in the game. I got almost zero response from any journalist that I personally contacted. The main article doing the rounds on Kotaku at the moment we were doing our Kickstarter campaign was that dust gets into consoles. Yes, dust is more interesting than your game or your Kickstarter campaign.

Bloggers, Twitchers and Youtubers

From EGX I had made lots of contact with Bloggers, Twitch players and Youtubers. These people played the game and enjoyed it enough to talk about it. I seriously underestimated how awesome these people are and how much they'll help you push your game out there. I would even go as far as saying make friends with these people more than the press, they're your biggest allies and they're the kind of people who would love to play your game and will support you if you're making something that they'll enjoy.

Exhibiting

While exhibiting we made lots of friends amongst the game devs who were there and could chat with them about their experiences. Lots of people came to our stand who were friends-of-friends and introduced themselves as such to me. This demonstrates the power of your own personal social network and just how small the world is.

Print out flyers and distribute them. We printed 1000 flyers to begin with, I read a lot of post mortems that said they had difficulty ditching their printed media. We had no such problems, in fact by halfway through day 2 we started running out and had to get another batch of 1000 printed and sent to us next day delivery. We distributed every single flyer and were actually running low again by the final day. We saw very few 'wastages' of our flyers, very few people threw it on the floor (and lots of them do end up like this). We suspect it's because of the strength of the artwork on the flyer itself, you could almost consider it like a mini-poster, it almost feels a shame to throw it away.

Plan your pitch in advance. I spent ages figuring out how to answer certain questions in advance. The most important one is "So what's this game about?". You'll be surprised at how tricky it is to come up with a quick, concise answer especially when there's so much cool stuff in the game you really want to tell people about. Well it's a .... and it's got... and it's.... oh and.... keep it short and snappy, practice it. Get friends to pose the question to you.

Make sure your team can do it too. You have a team don't you? Don't go solo. If you need the loo, you could miss out on a youtuber or member of the press wanting to chat to you.

This brings us onto our next dilemma. The backing board, which we paid a lot for - just had to come home with us. We couldn't bear to part with it; after all, we had worked hard on this and it would be a terrible waste. So I ended up using Shiply to find us a courier to send it back home with.

Steam Greenlight

Steam Greenlight is a process you need to go through in order to get your game published on steam. It has a voting system where gamers can choose if they would buy the game, wouldn't buy the game, or will wait till later. Our Greenlight launched with old graphics - because we were still tied up on the graphics front. Some people later noted that the graphics changed, that's because we were still working on it.

I have no video editing skills so asked around a few places to help me with both the Greenlight and the Kickstarter pitch video. I figured it would be better to get someone who knew what they were doing to do it for me rather than I make a mess of it myself. Most companies wanted to charge me in excess of £1500 for their services, with a budget of £1000 being "insufficient".

These companies have such production overheads that brings their cost to this amount, they'll go full movie set on you - in the end I found some local students who just turned up with a camera and a mic and did the editing for me for a reasonable quality. It also helped that they were just as geeky as me and into what I was making. Absolute life savers.

Fitting in time to do video shoots, prepare press kits, trailer videos, create pitches, organise exhibitions, submit posts, write articles and so in is very demanding, bearing in mind that I had to also bug fix and prepare a build for the actual exhibition.

Despite all this, you will still have people complain about everything you do. One person we saw on Greenlight only had one single first person shooter game in their library and was actively bad-mouthing every single RPG Greenlight that went up going as far as stating that some developers should "quit the industry". It's actually a really horrible experience and can be massively demotivating for some developers, but thankfully most people were overwhelmingly positive about what we were making.

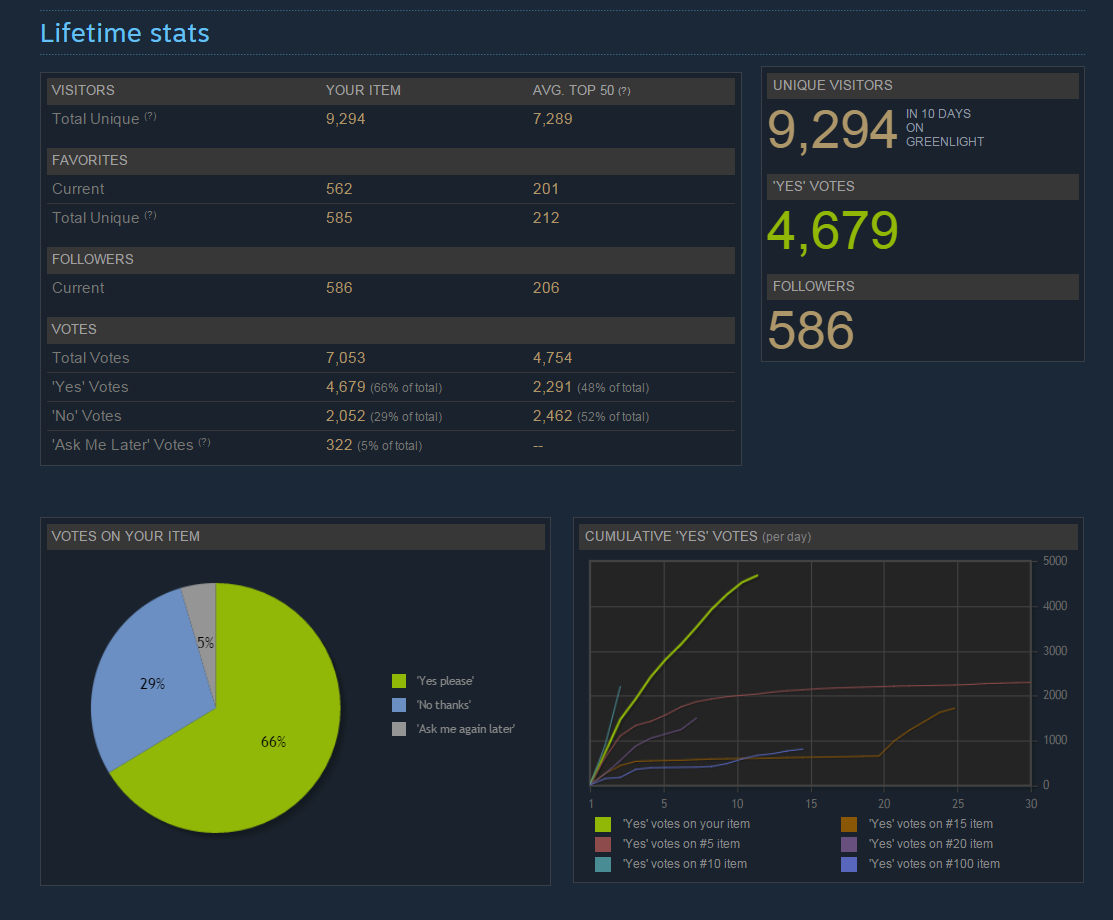

The above is our stats as of being Greenlit. Our Greenlight was wildly successful. We were in the Greenlight machine for only 10 days. We've heard tales of people being stuck on Greenlight for months. Many people voted yes, and of those that voted no - we suppose the majority of them simply aren't interested in this sort of genre/style (which is totally cool). The remaining no votes (of which we think are a minority) are from the trolls. It's the Internet, they're going to be there, don't feed them.

Mentally, Greenlight is nerve-wracking. You have no idea if you're going to make it or not and if you're like me you keep going back to the page every 5 minutes to see how it's going.

We launched this about a week prior to EGX and Kickstarter, we wanted to use it as a springboard to get some eyes on the Kickstarter campaign. Very little traffic to the Kickstarter campaign came from Greenlight. In fact, you get more traffic to your Greenlight campaign from Kickstarter than vice-versa.

Clicking yes/no is free. Putting money down for a product that's not made already is a different ball-game.

Most of our traffic came from Greenlight itself, and another good portion came from our social media. The rest was simply word of mouth as it spread through forums as gamers started talking about it.

Do be careful not to spam people or blatantly advertise in places where you shouldn't. I had to tell one of our team members to calm down a bit as it was having an adverse effect (annoying the hell out of people is a big no-no in my books) - don't do this.

Kickstarter

Kickstarter was an interesting experience. It didn't pan out the way I had hoped (we were unsuccessful in obtaining funding) but I learned a lot about the process and the community behind it.

The community itself - is awesome. Most of your backers will do what they can to help you out, through spreading the word or even giving you advice. Some people will give you bucket loads of information which can be overwhelming. Most do forget that you're still working full time, so it's difficult to keep up with updates.

If I had more time in the lead-up to the Kickstarter campaign, I would've better pre-planned the updates. Instead, we were writing them during the course of the campaign.

Lots of people said "when are you going to spread the word", if only it was that easy. We had already put out as much as we could. We attended exhibitions, followed up every lead for people who wanted to talk to us and tried reaching out to the press. But we were met with absolute silence from most.

Budget Outline

At first, my Kickstarter didn't have information on how we were going to break down the costs. I ended up having to add this in because people were finding it difficult to justify how an indie developer can spend £68,000 on producing a game. With such a large scope and attention to artistic style, this game is actually a very massively slim budget. £68k was literally the sum I needed to make the bare-minimum in the space of a year.

Adding this information helps people understand just what your game costs and helps your backers trust you know what you're doing. What disturbs me more is the number of Kickstarters that are asking for lower figures. Can they actually make the game on such a small budget?

Depends on the game, if it's a small 3 month project, maybe so (in my case, I would just absorb the cost myself for such a short time-scale). But for the majority of games, I suspect the budget is woefully low. So either the game has to be already quite well developed, or they need to have an additional source of funding.

What this does do however, is create a situation where people's expectations of the cost of an indie game lowers - causing some developers to ask for less funds (because that's what they think they'll achieve realistically) and then failing to deliver because they don't have enough funds, further lowering consumer trust in developers.

Never ask for less than you need. I would rather be unfunded but know I can make this game than be funded and know that I can't.

Timescale

Some people were impatient over the timescale. One person said they'll be "dead" if they had to wait till 2017. (Sadly they'll be waiting even longer now, I hope they can hold out). In reality - if you completed Kickstarter late October, you wouldn't see the funds until they've processed (about a month) and you're starting work late November / early December. So one year from then is December 2016, so a release in early 2017 sounds like a long way off, but really isn't.

We scoped all the work and figured out just how long it would take for us to do it. It would essentially be a year non-stop mental work.

In some respects, the failure of the Kickstarter is a positive. It means that our deadlines are not as tight as they were before, meaning we can actually spend more attention to detail.

The two games that were next to us at EGX, Mushroom 11 and Beyond Flesh and Blood were 3-4 years in production. This seems to be the normal sort of turn around time for a game of decent quality to be produced. I suspect the same may be true for myself, especially considering my current circumstances (working a full time job, then jumping onto Tears of Avia in the evenings/weekends).

Exposure = Success

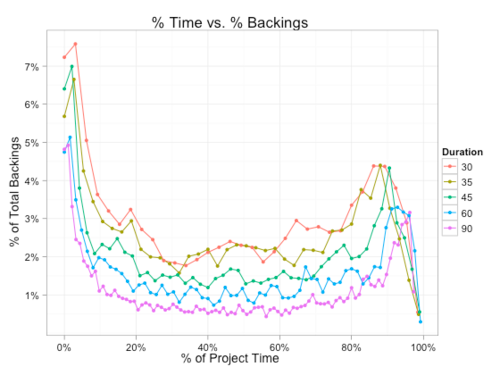

We followed a lot of guides in the construction of our Kickstarter. Kickstarter recommends 30 days for your campaign and shows you a chart that looks like the following:

This is a typical graph of trends in a Kickstarter. Massive initial push and then a period of quietness, then a last minute boost at the end.

That last minute boost typically comes from the 48 hour reminder email that Kickstarter sends out to people who are interested in the project but haven't pledged yet (either unsure, want to see how it pans out or simply haven't been paid that month yet).

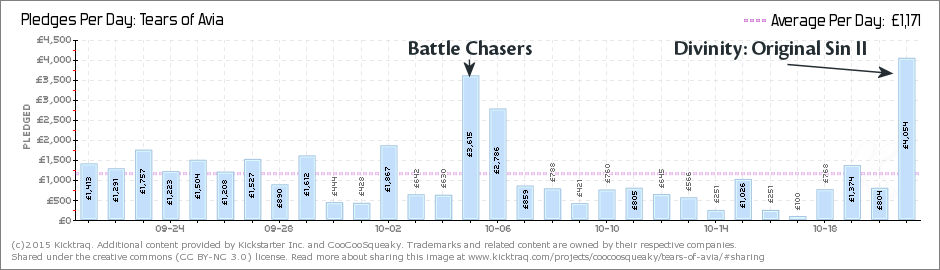

Let's see our chart on kicktraq

Our chart looks nothing like what Kickstarter says it should look like. We launched to an immediate trough. What went wrong?

Exposure.

The campaign itself was fairly solid - evidenced by the fact that people weren't shy to pledge (some backers even wrote to me to say the same). Our tiers seemed expensive to a lot of American backers due to the exchange rate between the GBP (£) and the USD ($) being somewhat non favourable. The figures on my Kickstarter were sensible and made sense in GBP, but may have seemed obscene to American backers.

This was problematic and a bit of an oversight on my behalf, I originally tried to balance the tiers such that they were affordable, yet meet the funding goal we needed to make with a reasonable number of backers. The GBP/USD exchange rate was far worse than I expected. Furthermore, once people back a tier on Kickstarter, it's incredibly hard to make changes to your campaign, meaning you're stuck with it.

However, this did NOT stop people who were passionate about the project from backing me, it may have deterred people who wanted a cheap game for a buck though.

The makers of Battle Chasers spotted us halfway through the campaign and mentioned us in one of their updates. People backed our project straight away.

In the last four hours of the project, Larian Studios spotted us and gave us a shout out on one of their Kickstarter updates for Divinity: Original Sin II. Look at that bar at the end of the chart. Four hours. Look. Just four. Four.

This is the power of exposure. Without it, you're in a trough.

People suggested using Thunderclap. Thunderclap is a tool that enables you to send out a message simultaneously across social networks via lots of supporters who back your cause. However, it's yet another campaign you have to drive traffic to. You'll have to get people to sign up for Thunderclap, back your Thunderclap campaign, then when it hits the threshold, everyone posts about you at the same time.

I'm sceptical as to how effective this is - when you're essentially pushing people to your Kickstarter campaign in the first instance. Coupled with the aforementioned observation that on Twitter, you need to post often to avoid getting lost in the sea over time, I couldn't see it as a way of driving new traffic.

The updates from Battle Chasers and Divinity were a real surprise, my sincere thanks to both developers.

I would recommend doing promotion exchanges with other Kickstarter campaigns (as I did) but what I didn't really think of doing was to seek out campaigns that were already funded and ask for their support too.

Kickstarter Marketing Agencies

Ever seen those Kickstarter campaigns that aren't of a major game, but have millions of dollars of backing flying by in facebook adverts? With clickbaity headlines like "This thing has amazed millions of people, get in quick before you miss out" - these come from Kickstarter marketing agencies.

When you launch a campaign, you will get spammed by them. Lots of people promising to optimise your campaign and even "save it". One such company promised to make your funding goal but with just a small percentage fee only if you make it.

It was pretty vague, so I decided to find out. After making contact - turns out they actually wanted $2,500 upfront then 35% of whatever you make at the end of your campaign. 35% is a kiss of death.

When you consider your costs for backer rewards and fulfilment, plus what you need for actual development you must think really carefully if you want to go this route. I'd even say you should budget it in, if your strategy to get exposure is this method.

But consider this - there are Kickstarter campaigns out there where 35% of what they get is purely to get your attention in the first place. I couldn't go this route. Not only would it have caused me to fail to deliver, I can't justify people putting such a large amount money down just to fund a marketing agency, not the game that I'm trying to make.

30 days vs way more days.

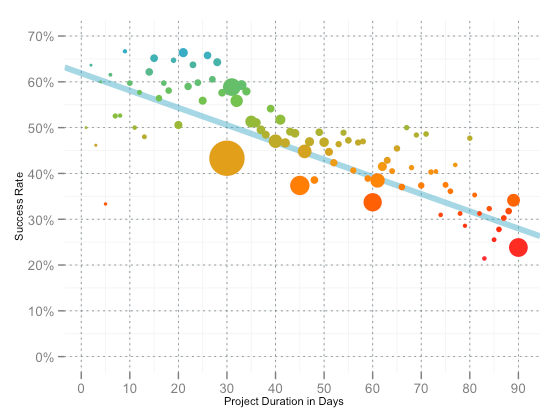

Kickstarter recommends 30 days for an optimum campaign length. I would say - yes and no.

The above chart shows the correlation between campaign duration vs success rate (the percentage of projects that make it). This chart is misleading and I was mislead.

For starters, it doesn't indicate what these projects asked for in terms of funding. It could be that someone asked for £50 in the space of 10 days and got it, after all, it's not too hard to raise such a short amount of money. There's absolutely no way to tell with this data.

I was in a trough, I managed to pull in at 53% of my goal and I had a 30 day campaign. If I did a 60 day campaign and troughed all the way, I may have even reached my goal.

That however, is a long road. In 30 days, I was struggling to put out content updates fast and furious. I was working a day job, get home to answer millions of emails and messages, somehow write content (which takes time, this article alone has devoured my afternoon) as well as press on with development.

Your time is squeezed, so doing that for 90 days is genuinely fatiguing. If you run a long campaign, you need to prepare for it very well to make sure it doesn't stagnate mid-way. Most people get itchy after a day or two of no updates, that's the sort of pace you have to keep up with. And usually, you wouldn't have pushed forward the game THAT MUCH in that space of time so you need to find other things to write about - that can be hard.

This goes back to my previous point, pre-plan your updates.

What to do after a failed Kickstarter?

Carry on.

Don't quit, ever. You've come this far, why stop now? I got two out of three, that isn't bad.

I'm pursuing other funding options. One company I spoke to failed their Kickstarter and have now brought their game to market thanks to investor backing. In the meantime, I'm working away from the prototype towards an early-game experience so that I can put it into the hands of investors/publishers without needing to guide them through it.

Most gamers savvy with the genre can pick it up and get it straight away, but it still needs work to make it accessible for the wider audience.

So I'm pushing forward, I'll keep doing this for as long as it takes, doing it the way I always have - in my spare time funding it out of my own pocket. Except now, I have some awesome people who are supporting me in doing so via Patreon (if you want to do the same, check my patreon out)

Being able to put something that plays more like a game and less like a prototype opens up more possibility for funding options. Possibly, a second round of crowdsourcing is also possible with more of the game completed (thus less budget required to complete it).

Either way, this game is going to happen, I'm not done yet.

Wow, what an adventure so far! Thanks for sharing and good luck.

This comment is currently awaiting admin approval, join now to view.