A lot of people have been asking for information about some of the mechanics in the latest release, so here we go. These are going to be long and detailed posts about some of the game mechanics - you have been warned. My approximate plan is to this week start with puzzle/riddle generation (part 1), finish it off with part 2 next week, then move onto a post about generating ziggurat interiors. We’ll probably then have an entry about designing the extra languages – aesthetically, not in terms of code – and at some point later, when languages are fully implemented, I’ll be talking about them.

So, this first entry will detail the design goals of the puzzles and the process of creating the puzzle solutions, checking the solution will be valid and assigning clues to them; next week’s entry will conclude this two-part series by covering how clues are generated and written by the game, and how to ensure clues are clear, even if they are cryptic (two apparently contradictory goals).

I had three objectives when beginning the process. These will also be applicable for future forms of puzzle too.

Firstly, all puzzles should be solvable on the first try. There must be no trial and error. Some puzzles may, later, come with traps of varying severity and lethality (traps will likely be integrated into puzzles for 0.4); they must be avoidable with perfect play. This is not to say they might not take a long time to solve, but you should always be able to submit the correct answer first time. If there is any ambiguity, there need to be more clues, or the puzzle needs reworking. Given the clues, puzzles can be cryptic, but they must never be ambiguous.

Secondly, the puzzle must have only one solution. This is not just because having multiple solutions makes a puzzle easier, but also because getting the software to recognize all solutions that meet the clue requirements on the fly, rather than upon the generation of the puzzle, was a far more challenging task.

Thirdly, all puzzles must use the smallest number of clues possible. That is to say that if the game provides you with four clues, but one is superfluous, it should be able to remove that clue and keep paring down clues until you have the bare minimum required. This once again increases difficulty, but also reduces the amount of data (potentially duplicated data) the player needs to process.

There are three stages to the puzzle, of which the second stage is the major focus. The first stage is deciphering the riddle – for example, understanding that “the creature of poison arrows sits north of the many-legged one” means “a frog is north of a spider”, which we’ll talk about next time because those phrases are generated quite late in the process. The second stage is working out the placement of all the different blocks based on the clues you’ve been given (which, as above, should be only just sufficient to solve the puzzle with), and the third stage (the most minor) involves maneuvering the blocks into position. The third is just a minor Sokoban puzzle in some situations, so let’s skip over that one.

The first stage in generating a puzzle is to determine how difficult a puzzle should be placed. There are two sizes of ziggurat, “medium” and “large”. I originally intended to have “small” ones as well, but I found them a little too small to really feel like a full dungeon (using “dungeon” in the broadest sense); whilst that feeling would decrease in future versions once I add more room types, for the time being we’re just going for medium and large. A medium ziggurat has four floors and a large has five. There are five different “levels” of puzzle, 1-5, of which level 5 are considered “boss” puzzles and can only be placed on the penultimate floor (so the third floor in a medium, or fourth floor in a large). The final floor always houses either a clue, or a secret item – in later versions there will be far more variety and these peaks will include treasure, loot, weaponry, various other items, and potentially “boss” level NPCs who have also made their way into that same ziggurat. For now, however, three ziggurats contain secrets, whilst the others contain clues directing the player towards those with secrets.

The floor the puzzle is being generated on determines the level of puzzle; harder puzzles appear on higher floors. It is weighted to give you a logical progression of puzzle difficulty in each ziggurat, but also to allow for unusually difficult puzzles to rarely appear on each floor (similar to “out of depth monsters” in Dungeon Crawl). I will focus on the placement in the later entry of ziggurat dungeons, but the game basically draws a route from door -> stairs or stairs -> stairs and places rooms of appropriate difficulty along that route. Some ziggurats will have a tougher combination of puzzles, some easier, but given that I’m making a procedurally generated game I certainly don’t mind a little variation, and once other factors are in play – such as traps in 0.4! – difficulty should equal itself out more easier than with just a single challenge from the puzzle room.

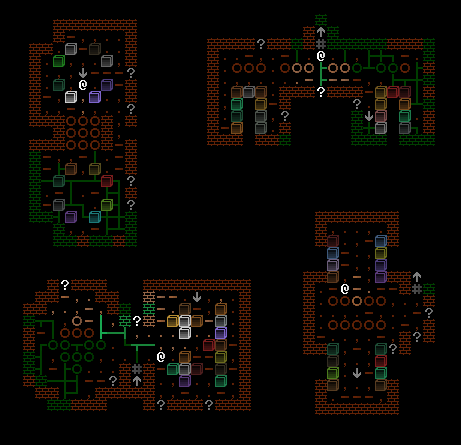

The next stage is to pick a puzzle. There are several for each level. For example, Level 1 puzzles can be 2×1, 3×1, or 4×2. Level 2 can be 2×2 or a “cross” (like the five dots on a die rotated 45 degrees). At the higher end, the Level 5 boss puzzles can be 12×1, 3×3, 5×2 or a “star” (3×3 with the middle removed but an extra pressure pad on each edge), as shown below:

Once it has chosen a puzzle shape, it then selects correct blocks at random from a series of all blocks. So, if we have a 2×2 puzzle, it might select a Full Moon, a Snake, a Spider and a Winter Tree. Full Moon might be classed as block a, Snake as b, Spider as c and Winter Tree as d (the puzzle being ab on the top level, then cd below, to form the 2×2 square). The game then picks from a variety of what I’ve been called “clue orientations”. For 2×2, for instance, it may pick a particular corner then give two definite orientations next to it. So, if it picks the top-left corner, it would generate a clue (details next week) that says the top-left is on the east of the top-right and north of the bottom-left. It would then know that the second clue needs to relate the bottom-right tile, but because the earlier two clues are directional, this final clue doesn’t need to be.

In any case where a non-directional clue can be used, the game prefers to do that because it’s automatically more difficult. Saying “X is west of Y” is simpler than “X is opposite Y” and having to figure out whether that is north, south, east or west according to the rest of the clue. However – and 0.3.1b fixed a few issues like this – it soon became clear you simply had to have some directional clues. For example, the 3×3 grid is symmetrical in all four orientations, to simply saying “opposite” for all clues would mean the clue could be solved in four orientations. I felt this both made the puzzles easier, and possibly more importantly, would actually be a lot harder for the game to check if there were multiple solutions. For more advanced sets of pressure pads, there are a large number of potential methods by which the game can produce the clues. For example, for a 3×3 grid, it might create a clue for the top row, a clue for the bottom, then go from there; or it might create a clue for the top-right corner, a clue for the bottom-left corner, then three more; or it might create a clue for the three in the middle (vertically) then work out from there. Obviously the larger the pressure pad pattern, the more clue orientations there are, but the harder it was to make sure all clue orientations can be solved. Despite my best efforts 0.3.0 had a few that couldn’t be solved, but those were all fixed for 0.3.1′s release. Lastly, each puzzle can only contain a particular block once, so you can never get two of the same block in one puzzle, although variations upon a theme – ziggurats of different sizes or trees of different seasons – are allowed. This is again to be remove ambiguity – if there are two frogs in a puzzle, there might be multiple solutions, which means trial and error might come into it, and that was unacceptable according to the design plans at the top of this entry.

Thus, once it has selected it blocks and gone through a number of possible permutations, it then develops the clues. Next week I’ll be going over this process, and the tricky balance between keeping clues cryptic, but also unambiguous.

Also, version 0.1.3c is out with a few small bug fixes, and one big one which nobody spotted but I realized was there, which I’m afraid breaks save compatibility. ENJOY, INTERNET! Until next week you can keep up to date on my devblog, Facebook page, or Twitter feed. The devblog is updated weekly or fortnightly generally on Mondays, Facebook a few times a week, and the Twitter roughly daily. Any thoughts, please leave them in the comments! Stay tuned...