This is a re-post of the YoYo Games tech blog where I am posting the dev diaries for Skein. I'll be posting all the articles so far written over the next week or so, then I'll be updating this weekly with the new ones as they are written.

The Big Idea

The idea for my game comes straight from my youth - Gauntlet and Gauntlet II. I loved those games! I loved them so much, that the first thing I ever made with GameMaker was a Gauntlet clone (hey, we've all cloned our favourite games, right? Best way to learn...). I've progressed quite a bit since I made my Gauntlet fan-game, and now tend to make smaller, mobile-friendly games that are on a less epic scale, but that game still holds a special place for me. To be honest, I've been wanting to revisit the idea for a while now, especially as GameMaker: Studio has better performance than the GM7 that I used to make my own fan-version... meaning more of everything. More effects, more gameplay and more enemies! So, that was decided then... I was going to make a game inspired by Gauntlet!

But what was it about Gauntlet in particular that got me so enthusiastic? The game was hugely successful, so what was it about the gameplay that kept people putting coins in the cabinet? Looking back, I seem to remember being in tension for a large part of the game. Tension caused mainly by time limits imposed on you by the game itself - your life is counting down as more and more enemies pile up behind a wall, and you have to choose to exit the level or use that key you have to open an area which you haven't explored yet, and then Death himself appears when you've taken too long to leave a level... These imposed limits forced the player to do everything as quick as possible while trying to balance finding the exit with the urge to explore the level and get more gold, which in turn caused tension in the player. Another key mechanic of Gauntlet is a subtle one, that also enforces this balance between fight and flight. You can't strafe. It's a small detail, but think about all the games you play and ask yourself if you can strafe in them? I'll bet the answer is "yes", but in Gauntlet it's "no". When you shoot, you can't run about, so it's run away or stand and fight! I think that that simple decision adds greatly to the tension of a Gauntlet game, and as such it was going to be a fundamental part of my game too.

If you're not a "golden oldie" and haven't played Gauntlet before, you can find the arcade version emulated here: Golden Oldie Arcade

But Wait...

Obviously when you decide that you are going to make a game, you don't just sit down and start hammering at the keys (or at least you shouldn't). That's a recipe for disaster as you quickly succumb to feature creep and distractions, so the first thing you should do is decide on the core mechanics for your game and get them down "on paper". These can change, and some flexibility will be required, but with a set of core goals and ideas, you will have a solid target to aim at and you will be less likely to start adding and changing things on a whim.

Before I got to that though, I needed to look at other games that fall into the same top-down-shooter / ARPG style that Gauntlet has, as well as a few others that fall outside of the core target genre, but that still have elements of interest. Note, I was not trying to clone Gauntlet, but rather capture some of things that made that game great and distil them into my own creation, so looking at other games, especially ones I loved to play (or hated deeply), will also help me clarify my ideas. Researching an idea can be very important as it gives you insight and perspective on your game, and can also help spawn new ideas for gameplay. I won't bore you with the details of every game I played, but after looking at the likes of Hammerwatch, Hero Seige, Lara Croft and The Guardians Of The Light, and Hand of Fate, I had a fairly good idea of what I wanted to do.

Before continuing, note the inclusion of Hand of Fate in that list. That game is a card game, and, on the surface, quite different to the idea I have, but it's a perfect example of something I mentioned earlier - playing games outside the scope of your base idea. If you look at the core of that game, it really has a lot of similarities in the mechanics to what I want to achieve: constantly decreasing health, procedural levels, rewards based on progress, etc... So, don't limit your research to a narrow section of games, but play anything that has inspired you or has fringe details similar to your idea.

The Design Document

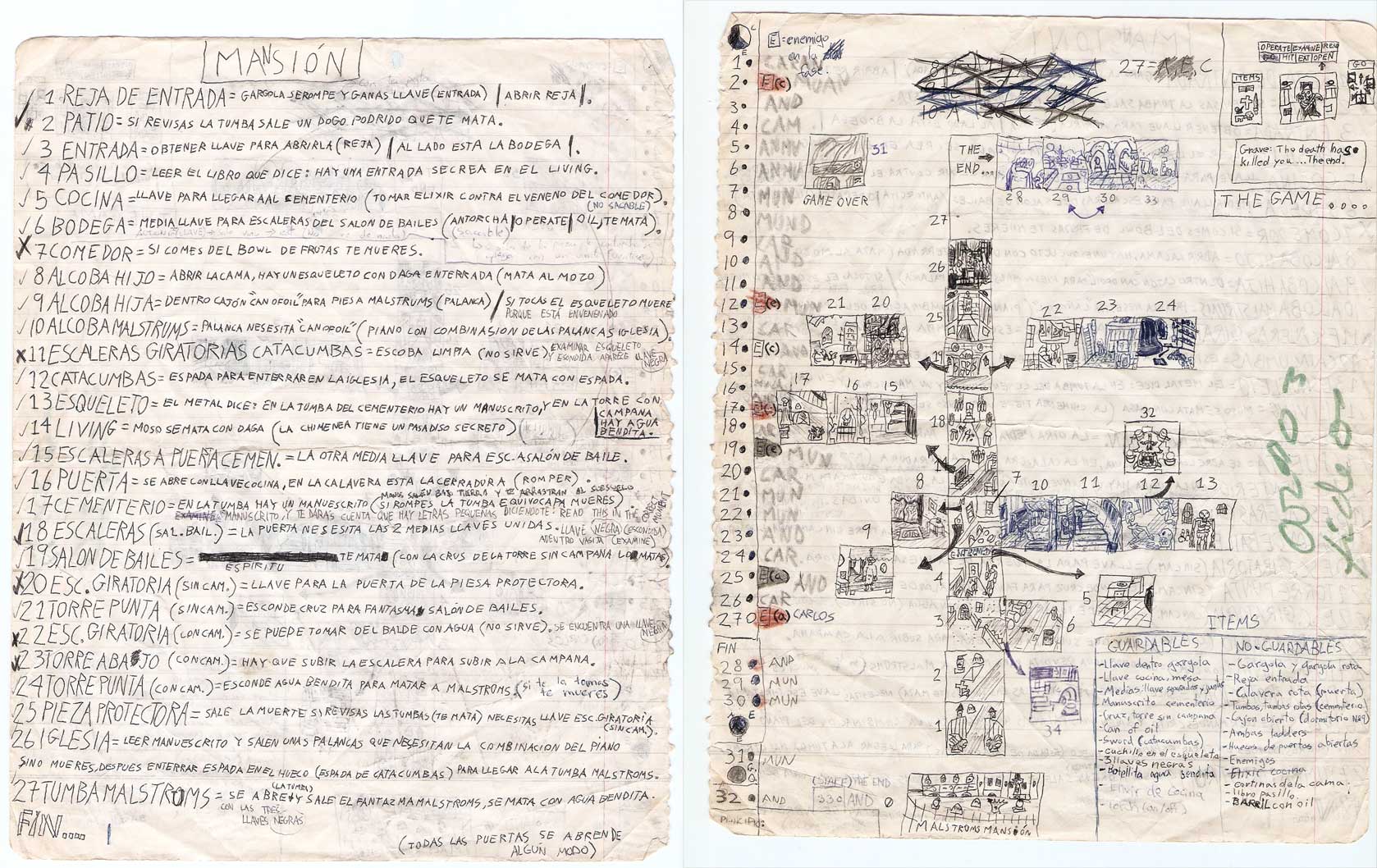

It was time for me to write out a design document. I feel this is an important step in any project, and although some people will say they can keep a project clear in their head, I think that having it written down somewhere gives a greater sense of focus and a proper goal to work towards. How you do write your design document is up to you, but I find pen and paper to be the best recourse - I like being able to scratch out and underline and draw connecting arrows to things, or add doodles, and the whole process feels more organic than sitting at a screen. I also don't tend to write more than two, and I try to keep them short - the first version is a draft and pretty damn messy, and the second is a tidy up and will be my main plan of action - however, how you do things is up to you, as long as you have a firm vision of how you want the final game to be and a how to get it done.

In the end, my own design doc was pretty short and contained the following points:

Make a top down fantasy action game with lots of enemies, traps, and magic. The game should be fast paced, have a lot of variety, but be very easy to play, so minimal controls (mobile friendly?). The game should generate content procedurally, rewarding progress through the dungeons with new content (spells, traps, enemies, rooms).

- The dungeon should be created procedurally and adapt to the "level" of the player, introducing new elements the further they progress

- Player can shoot or use melee attacks, and has a single special move that requires mana.

- Player can use magic, but only on a limited basis (spells? Pickups?)

- Player has different classes which will affect the gameplay in a minor way (Mage, Wizard, Archer - equivalent to easy, medium, hard).

- Player health goes down constantly, so potions/food are required

- Enemies spawn from "generators" and are generally dumb (the challenge is in the number)

- Enemies should come in a large variety of "flavours", each with subtle - or no! - differences in how they fight/move

I could go on from here and start filling out details, adding a story, planning rooms and content, etc... but for me that is something I'll do "on the march". Some people do like to have a full blown 100%-set-in-stone plan of action before starting, and that's fine, but it's not me! If I did that I fear that I'd spend more time on the design document than the actual game, and eventually nothing would get done, so like I say, it's up to you what you write, as long as you have some form of plan to stick to.

Getting Started

Now I have a design document for what I want to do, but I still haven't prioritised things into a plan of action, so that's what I need to do next. Since I want the game levels to be created procedurally, and the rest of the core mechanics will all stem from that, it seems the logical place to start. Then I reckon I'll do player movement and after that add some bad guys and then finally the magic system. Doing things in that order will more or less cover the core game mechanics as outlined in the design document, and permits me to compartmentalise the code as much as possible.

I also made a decision at this stage to make the game "low-res", with a base resolution of 160x120, and then scaled up to fit the display. I created a Sokoban game some time ago with a lovely 8x8px style (there is a screenshot above), and I felt that this would also work well with the game I had in mind. I had also licenced some static sprites from Oryx Design Labs which I realised would fit in with the whole low-res-rogue-like feel that I wanted. Those sprites are great and I could animate and adapt them easily enough, saving me a lot of artistic work.

With those decisions taken, and a clear plan to follow, I could finally fire up GameMaker: Studio and start working on my game. The first and most important thing to work on was obviously going to be generating the levels procedurally, which meant that I had to choose a system that would be flexible and give interesting levels. However I had never done procedural generation in a game and before writing a line of code it was off to do some more research on how proceedural generation works. This was interesting stuff, and I tried prototyping several systems like the drunken walk or room chunking (the classic GameMaker game Spelunky uses this - break a room into pre-designed "chunks" and then swap them about), but none of them did what I wanted.

Then I hit on the "magic formula" that would create the core of my game - Binary Spatial Partitioning (also known as Binary Trees) - which we'll discuss in much greater depth in the next news post.